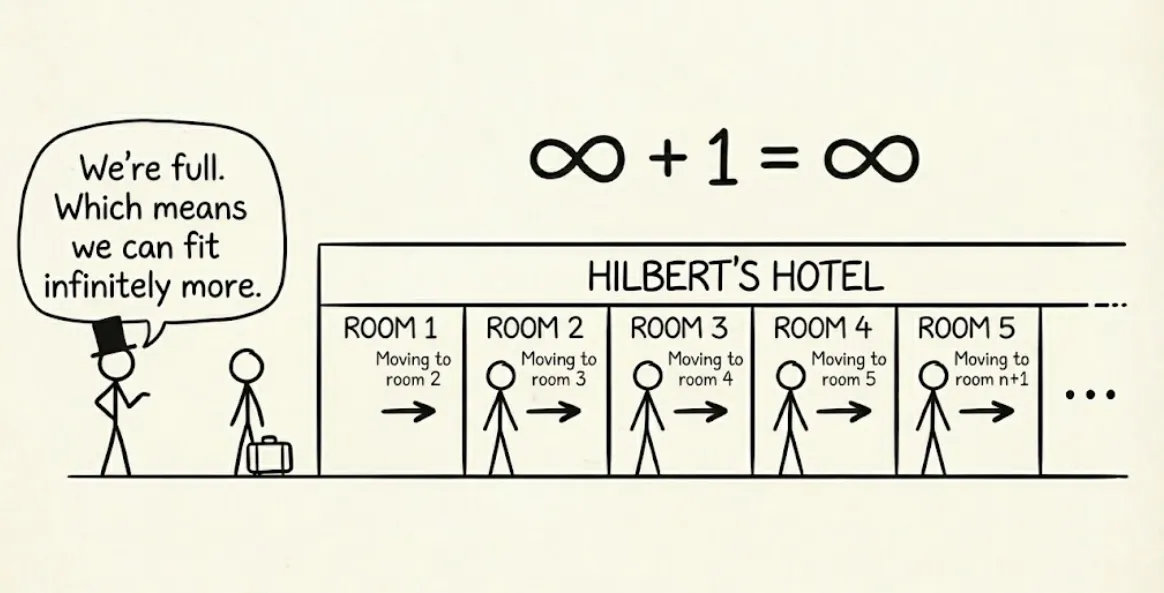

Imagine a hotel with an infinite number of rooms… all occupied. But since it’s infinite, you would think you can always make room for more guests, right?

Hilbert’s Hotel

The Hilbert Hotel paradox was introduced by mathematician David Hilbert in the 1920s to illustrate the bizarre properties of infinite sets.

The hotel has infinite rooms — numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 … and every single room is occupied. No vacancy sign up.

A new guest arrives. In a normal hotel, you’d turn them away, because it’s full. But this is an infinite hotel. What can the manager do? He is good at maths.

He asks every guest to move to the next room.

- Guest in room 1 moves to room 2

- Guest in room 2 → room 3

- Guest in room 3 → room 4

- … everyone shifts by one

Now room 1 is empty. The new guest checks in.

We added 1 to infinity and got infinity.

+ 1 =

We can do the same for any number of finite guests.

+ 100 =

Infinite new guests

Now an infinite bus arrives with an infinite number of guests (numbered 1, 2, 3 …). The hotel is still full. What does the manager do?

He asks every current guest to move to the room number that’s double their current room number.

- Guest in room 1 → room 2

- Guest in room 2 → room 4

- Guest in room 3 → room 6

- …room n → room 2n

Now all the even rooms are full, and all the odd rooms (1, 3, 5, 7, …) are empty. Infinite empty rooms! The infinite bus guests check into odd-numbered rooms.

We added infinity to infinity and got infinity again.

+ =

Infinite infinite buses

Then one night, the manager’s nightmare happens: infinite buses arrive, each with infinite passengers. That’s infinity × infinity guests.

Can we fit them? The manager thinks hard and long and he comes up with a clever plan.

He creates a table with buses as rows and seats as columns:

| Seat 1 | Seat 2 | Seat 3 | Seat 4 | … | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bus 1 | (1,1) | (1,2) | (1,3) | (1,4) | … |

| Bus 2 | (2,1) | (2,2) | (2,3) | (2,4) | … |

| Bus 3 | (3,1) | (3,2) | (3,3) | (3,4) | … |

| Bus 4 | (4,1) | (4,2) | (4,3) | (4,4) | … |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

Now he assigns them by going diagonally —

- Passenger (1,1) → room 1

- Passenger (1,2) → room 2

- Passenger (2,1) → room 3

- Passenger (3,1) → room 4

- Passenger (2,2) → room 5

- Passenger (1,3) → room 6

… and so on. By traversing the diagonal, he creates a systematic way to assign every passenger from every bus to a unique room number.

We fit infinity multiplied by infinity and still got infinity so

× =

The guests we can’t accommodate

Then comes the bus full of guests whose names are real numbers between 0 and 1 (like 0.5, 0.333…, π - 3, √2 - 1, etc.).

The bus driver claims he has infinite passengers — each with a unique real number as their name. The manager scratches his head and answers “Sorry, we’re full.” And the bus driver is like, “what do you mean? Isn’t this an infinite hotel?”, then the manager tries to explain why he can’t fit them.

Cantor’s diagonal argument

Georg Cantor proved in 1891 that the set of real numbers is uncountably infinite, meaning you cannot make a list of all real numbers.

The bus driver claims to have a list of all real numbers between 0 and 1. They write it down —

- 0.254213562…

- 0.718281828…

- 0.141592654…

- 0.732050808…

- 0.618033989…

- 0.693147181…

- 0.577215664…

- 0.915965594..

…

Then the manager says “Hold on, I’ll write the name of the passenger that is not on your list.”

The diagonal trick

- Take the first digit of the first number - 2

- Take the second digit of the second number - 1

- Take the third digit of the third number - 1

- Take the fourth digit of the fourth number - 0

- Continue down the diagonal — 3, 7, 6, 9 …

Now change each digit (say, add 1 (wrapping 9 to 0)):

- 2 → 3

- 1 → 2

- 1 → 2

- 0 → 1

- 3 → 4

- 7 → 8

- 6 → 7

- 9 → 0

The new number: 0.32214870…

The manager tells the driver that this number is not in your list because —

- It differs from the 1st number in the 1st decimal place

- It differs from the 2nd number in the 2nd decimal place

…

- It differs from the nth number in the nth decimal place

You claim you listed all real numbers, but I just found one you missed. Your list is incomplete.

There is no way to list all real numbers — you’ll always miss some. The bus driver is disappointed. The real numbers are uncountable. They form a larger infinity than the natural numbers.

Countable vs uncountable infinity

Cantor distinguished between two types of infinity:

ℵ₀ (Aleph-null): Countable infinity

The size of the natural numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, …

Countable means you can list them in a sequence (even if the sequence is infinite). Examples:

- Natural numbers: 1, 2, 3, …

- Even numbers: 2, 4, 6, …

- Integers: 0, 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, …

- Rational numbers (fractions): 1/1, 1/2, 2/1, 1/3, 2/2, 3/1, … (Cantor’s clever zig-zag ordering)

All these sets have the same size as the natural numbers. They’re all countably infinite, all of size ℵ₀.

𝔠 (The continuum): Uncountable infinity

The size of the real numbers. Bigger than ℵ₀.

Examples of uncountable sets:

- Real numbers

- Irrational numbers

- Real numbers between 0 and 1

- Points on a line

- Points in a plane (same size as a line — another Cantor result)

These cannot be listed. They’re too big. There are “more” of them than natural numbers, even though both are infinite.

How can one infinity be bigger than another?

This seems paradoxical. Aren’t infinite things all equally… infinite?

Apparently no. Two sets have the same size if you can create a one-to-one correspondence (bijection) between them.

Natural ↔ Even

Natural numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …

Even numbers: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, …

Pairing: n ↔ 2n

Each even number can be mapped to a unique natural number. So both sets have the same size, ℵ₀.

Natural ↔ Integers

Natural numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, …

Integers: 0, 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, …

Pairing:

- 1 ↔ 0

- 2 ↔ 1

- 3 ↔ -1

- 4 ↔ 2

- 5 ↔ -2

…

Each integer can be paired with a unique natural number. So again both sets have the same size, ℵ₀.

Natural ↔ Rational

This one was surprising. There are “infinitely more” rationals than naturals (between any two naturals, there are infinitely many rationals). Yet they’re the same size.

Cantor arranged rationals in a grid and counted them diagonally:

1/1 1/2 1/3 1/4 1/5 ...

2/1 2/2 2/3 2/4 2/5 ...

3/1 3/2 3/3 3/4 3/5 ...

4/1 4/2 4/3 4/4 4/5 ...

...He zig-zagged through: 1/1, 2/1, 1/2, 1/3, 2/2, 3/1, 4/1, 3/2, 2/3, 1/4, …

This creates a list of all rationals, mapping each rational to a natural number. So rationals are also countable, size ℵ₀.

Natural ↔ Real

No pairing exists. This is what the diagonal argument proves. Real numbers are fundamentally larger. Size 𝔠, not ℵ₀.

The hierarchy of infinities

Cantor didn’t stop there. He showed there are infinitely many sizes of infinity, each larger than the last.

Power sets

Given a set S, the power set P(S) is the set of all subsets of S.

Cantor’s Theorem: The power set P(S) is always strictly larger than S, even if S is infinite.

Starting with natural numbers (size ℵ₀):

- ℵ₀: Natural numbers

- 2ℵ₀: Power set of natural numbers (same size as real numbers, size 𝔠)

- 2𝔠: Power set of real numbers (even bigger!)

- 2(2𝔠): Power set of the power set (bigger still!)

- …

This creates an infinite ladder of infinities:

ℵ₀ < 2ℵ₀ < 2(2ℵ₀) < 2(2(2ℵ₀)) < …

Each step is a strictly larger infinity. There’s no largest infinity — you can always take the power set and get something bigger.

The Continuum Hypothesis

Cantor knew:

- ℵ₀ is the size of natural numbers

- 𝔠 (the continuum) is the size of real numbers

- 𝔠 > ℵ₀

He also knew 𝔠 = 2ℵ₀ (the power set of natural numbers).

Then he thought — Is there an infinity between ℵ₀ and 𝔠?

This is the Continuum Hypothesis (CH): There is no set whose size is strictly between ℵ₀ and 𝔠.

Cantor spent years trying to prove or disprove it. He couldn’t.

In 1940, Kurt Gödel proved you cannot disprove CH using standard axioms (ZFC).

In 1963, Paul Cohen proved you cannot prove CH using standard axioms.

The conclusion: CH is independent of the axioms of set theory. You can assume it’s true or false, and both lead to consistent mathematics.

It was shocking. It means the Continuum Hypothesis is neither true nor false — it’s undecidable within our standard mathematical framework. You get to choose which mathematical universe you live in.

The aleph numbers: Naming infinities

Cantor invented a notation for infinite cardinalities using the Hebrew letter aleph (ℵ):

- ℵ₀ (aleph-null): Size of natural numbers

- ℵ₁ (aleph-one): The next larger infinity

- ℵ₂ (aleph-two): The next one after that

- ℵ₃, ℵ₄, ℵ₅, … continuing forever

The Continuum Hypothesis asks: Is 𝔠 = ℵ₁? Or are there infinities between ℵ₀ and 𝔠?

We don’t know. We can’t know (given current axioms). It’s one of the deepest mysteries in mathematics.

Cantor’s legacy and personal tragedy

Georg Cantor (1845-1918) revolutionized mathematics with set theory and transfinite numbers. He proved that infinity isn’t a singular concept but a hierarchy of increasingly large infinities.

His work was initially controversial. Mathematician Leopold Kronecker, his former teacher, called him a “corrupter of youth” and opposed his ideas viciously. Henri Poincaré called his work a “disease.” Some mathematicians thought Cantor was destroying mathematics.

Cantor suffered from depression and spent time in sanatoriums. The academic backlash and his inability to solve the Continuum Hypothesis took a toll. He died in 1918 in a sanatorium, poor and largely unrecognized.

Today, Cantor’s work is foundational. Set theory is the bedrock of modern mathematics. His insights into infinity are considered among the most profound in mathematical history.

David Hilbert, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, famously said: “No one shall expel us from the Paradise that Cantor has created.”

Why this matters beyond mathematics

Cantor’s infinities aren’t just abstract curiosities. They have implications:

Computer science

Turing’s proof that the halting problem is undecidable uses similar diagonal arguments. Many undecidable problems in CS trace back to Cantor’s ideas.

Physics

Infinity appears in physics (singularities, infinitely small, infinitely dense). Understanding different sizes of infinity might be relevant to quantum mechanics and cosmology.

Philosophy

What does it mean for something to be “larger than infinite”? Cantor’s work touches on deep philosophical questions about the nature of existence, sets, and mathematical truth.

Theology

Cantor himself saw theological implications. If infinities come in different sizes, what does that say about concepts like eternity or the infinite nature of God?

These questions remain open.

Back to Hilbert’s Hotel

Let’s go back to our hotel. Suppose infinitely many guests leave. How many remain?

It depends on which guests leave.

- If all guests in even-numbered rooms leave, infinitely many remain (odd rooms).

- If all guests in rooms greater than 100 leave, 100 remain.

- If all guests leave, zero remain.

This is why subtracting infinity from infinity is undefined.

- ≠ 0 necessarily.

Infinity doesn’t behave like normal numbers. It’s not a number at all — it’s a concept, a direction, a size, a paradox and that is why it’s my favourite number.